Original on May 11, 2019 - Revised on Nov 14, 2021

In 2013, my wife, Sumi, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In the US about 6.2 million people have Alzheimer’s. Out of those, about 5% (300,000) have a younger onset of the disease. That’s when someone develops the disease under the age of 65. Sumi, being 59 at the time of her diagnosis, is one of those 5%.

My wife became a Person With the Disease, or PWD—someone with Alzheimer’s.

And I, on the other hand, became a Care Partner—someone who takes care of his or her spouse who is a PWD.

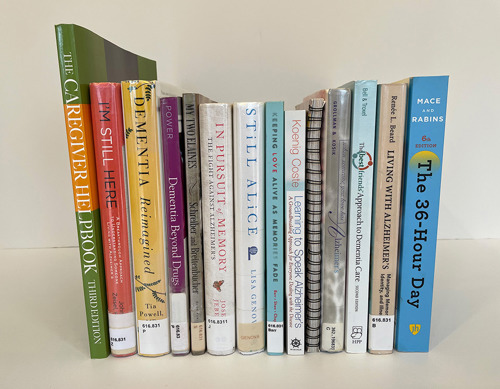

At the time of her diagnosis, Sumi and I had been happily married for over 40 years. Initially, I hoped for a misdiagnosis. But as time went on I educated myself by reading as many books as I could find on Alzheimer’s. I came to accept Sumi’s condition.

Other than brief periods where I would help Sumi in times of normal sickness, I had done little caregiving. Alzheimer’s changed this. While at first I wanted to change Sumi’s behavior, I came to realize I needed to instead change myself. I needed to tame my alpha-male tendencies to care for her.

Eventually, I turned to soul searching and reflection. This technique got us both through the initial years of our Journey.

Care Partnering is like attempting to scale a challenging mountain. Each year that goes by I climb to greater heights. Even though I have stumbled many times, I’ve also learned from other caregivers who are even higher up this mountain than me. At the same time, I have shared my knowledge with other caregivers who are in the early stages of their own Journeys and are at a lesser height.

In 2015, I began to write more formally about Sumi’s disease and my experiences as a Care Partner. I continue to write with three main objectives:

1. Increase awareness of Alzheimer’s to fight the stigma attached to it.

2. Share my thoughts and feelings. This allows me to process and channel my emotions, document the changes we go through, and share glimpses of our lives with others.

3. Let my writing be a barometer of my own health. A Stanford Study shows about 40% of caregivers die before the person they are caring for does.

I write “in the moment” to help process my emotions. I find it therapeutic. From my writing, I develop stand-alone essays. Our Alzheimer’s Journey: The Grieving Process is one of the 30+ essays I have written so far.

My essays can be read on my website: https://myjouneywithsumi.com

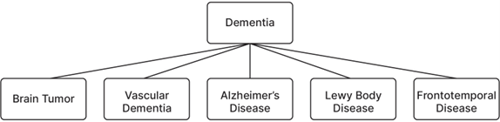

To truly understand Alzheimer’s, I first needed to understand the term dementia. As people age, it’s normal to lose some of our neurons—the connections in the brain that help people function. People with dementia, however, experience a far greater loss than normal. Many neurons stop working and the connections between brain cells are lost and eventually die.

At first, symptoms can be mild. But over time they get worse resulting in a serious loss of the cognitive functions that allow them to perform daily tasks. It causes changes in memory, language, personality and mood swings and executive functions like planning, organizing and attention span. It impairs visual acuity and spatial skills, judgment and reasoning.

Alzheimer’s is a type of dementia. To help understand this, think of the word flower. Just like flower is the generic name for various types of flowers, dementia is the an umbrella term that describes a collection of symptoms that are caused by disorders that affect the brain.

About 20% to 70% of dementia cases are considered Alzheimer’s. Other major types of dementia and their percentages are: Vascular (15% to 20%), Lewy Body (2% to 20%) and Frontotemporal (2% to 4%). Accurate diagnosis can be difficult since symptoms are similar among the different types of dementia. They can also vary from person to person.

To make a dementia diagnosis, doctors may ask for a medical history, a complete physical exam, and then order neurological laboratory tests.

Dementia is progressive and currently there is no cure. It is eventually fatal. But luckily, some treatments are available. If you, or someone you love, is suffering from dementia, speak to your doctor to find out what treatments might work best for you.

Through my readings, I found some factors that increase the risk of developing dementia. The risk factors that can’t be changed include age, family history, and Down Syndrome. The factors that one might be able to control are diet and exercise, excessive alcohol use, cardiovascular preconditions, depression, diabetes, smoking, air pollution, head trauma, sleep disturbances, and vitamin and nutritional deficiencies. Certain medications can worsen memory.

For more information, on page 89 I’ve included a diagram on the four common types of dementia. They are from the US Department of Health and Human Services—the National Institute on Aging’s website: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/ infographics/understanding-different- types-dementia.

As I learned more about Alzheimer’s disease, I found there are three stages to be aware of. The early stage (0-2 years of having the disease), the middle stage (2-7 years), and the late and final stage (7-10 years).

Early on, symptoms to look out for are:

• problems coming up with the right word or name

• trouble remembering names when introduced to new people

• increased challenges when performing tasks in a social or work setting

• forgetting material that was just read

• losing or misplacing valuable objects

• trouble with planning or organizing

As time goes on, the disease progresses to the middle stage. Symptoms show as:

• forgetfulness of events or even about one’s own personal history (like address, telephone number, their high school or college name)

• feeling moody or withdrawn— especially in socially or mentally challenging situations

• confusion about the day or about where they are

• needing help choosing proper clothing for the season or different occasions

• trouble controlling bladder and bowels

• changes in sleep patterns like sleeping during the day and becoming restless at night

• an increase in wandering and getting lost

• personality and behavior changes, for example an increase in suspiciousness, delusions, or compulsions. There could also be repetitive behavior like hand- wringing or tissue shredding

|

Early Stage (0-2 Years) |

Middle Stage (2-7 Years) |

Late Stage (7-10 Years) |

|

Problems coming up with the right word or name |

Being forgetful of events or personal history |

Requires round-the-clock assistance with the activities of daily living (ADLs) |

|

Trouble remembering names when introduced to new people |

Feeling moody or withdrawn, especially in socially or mentally challenging situations |

Not able to communicate needs, discomfort and pain |

|

Challenges performing tasks in social or work settings |

Being unable to recall information about themselves like their address or telephone number, and the high school or college they attended |

Trouble controlling bladder and bowel movements (incontinence) |

|

Forgetting material that one has just read |

Experiencing confusion about where they are or what day it is |

Lose awareness of recent experiences as well as of their surroundings |

|

Losing or misplacing a valuable object |

Requiring help choosing proper clothing for the season or the occasion |

Become vulnerable to infections, especially pneumonia |

|

Increasing trouble with planning or organizing |

Having trouble controlling bladder and bowels |

Changes in physical abilities |

|

|

Experiencing changes in sleep patterns, such as sleeping during the day and becoming restless at night |

|

|

Showing an increased tendency to wander and become lost |

||

|

Demonstrating personality and behavioral changes, including suspiciousness and delusions or compulsive, repetitive behavior like hand- wringing or tissue shredding |

The symptoms Sumi exhibits are highlighted in yellow in the chart above. Please keep in mind that the chart is shown for a 10-year duration. If life expectancy of the PWD is less than 10 years, the stages will be compressed and vice versa.

And then the disease progresses into the late and final stage. This includes:

• needing round-the-clock assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs)

• not being able to communicate needs, discomfort, and pain

• a loss of awareness of recent experiences and surroundings

• trouble controlling bladder and bowel movements (incontinence)

• changes in physical abilities

• an increase in vulnerability to infections

As Sumi is in her 9th year with Alzheimer’s she is in the late stage of the disease. Physically, she is in very good health and she is not on any medications.

Since Sumi is not able to communicate her needs, discomfort, and pain, I have become a super detective. I read non-verbal cues through her body language. With my career as a problem-solving engineer, I am a classic left-brainer. I am logical, analytical, objective, and in pursuit of excellence. As a Care Partner, though, I have started to use my right brain more. I rely on feelings, intuition, love, compassion, patience, and other non-verbal cues.

Sumi sometimes screams to get my attention or express her displeasure. Rather than getting annoyed by it, I remind myself that she has strong lungs and powerful vocal cords. Someday in the future, when she becomes weaker, that won’t be the case. Then, I will wish she could scream. This type of mindfulness gives my thoughts equilibrium and helps me process emotions.

Another example is how before her disease Sumi’s snoring would annoy me. But when she snores now, I find it comforting. She is sleeping soundly and in those moments I can attend to other things.

When people go through life-changing events, they experience a range of emotions and grief. These emotions range from anxiety, confusion, fear, frustration, withdrawal, nervousness, and sometimes depression. These emotions are natural and part of the grieving process. Everyone grieves differently, both in magnitude and duration.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, a Swiss-American psychiatrist and pioneer in near-death studies, established five stages of grief after the loss of a loved one. They are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This model was written about the grief a person experiences after a death, when a loved one is gone. But for Care Partners and those close to someone with Alzheimer’s, the grieving process is different.

We still have our loved ones with us. But they are dying a slow death, month by month, and year by year. It is like dying from a thousand cuts. You are always living with a new version of your loved one. Not the one you have in your memories with all the experiences you shared or the same person who had the same hopes and dreams as you.

As a Care Partner, I grieve for the loss of my former Sumi. And I am learning about my new Sumi, as she is now. But as the disease progresses, I will also lose this new Sumi. I will grieve for the loss of each Sumi as the years go by, throughout our Journey.

As I have experienced this grief, I saw how the intensity of it is very high in the initial years. It is like riding a rollercoaster of mixed emotions. Eventually, acceptance and management are obtained and can even come while a loved one is still alive. But there are many steps involved, such as acquiring Care Partnering knowledge, employing strategies for the safety and well-being of a PWD, cultivating a creative problem-solving mindset, and in the process gaining caregiving confidence.

In conjunction with Elisabeth Kubler- Ross’s grieving model, I like a simple acronym for the grieving process called SARA:

Shock Anger Reflection Acceptance

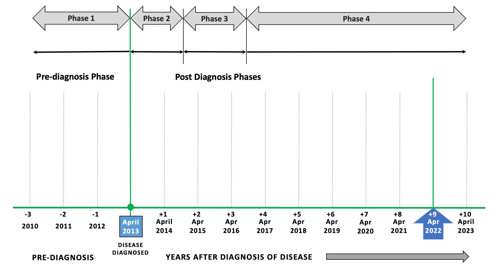

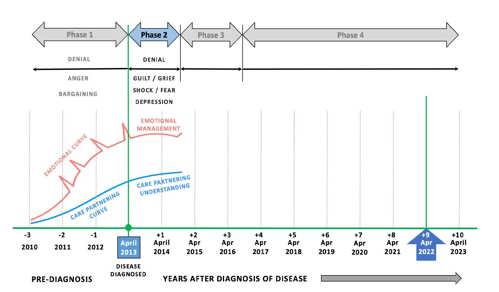

To dive deeper into the relationship between the intensity of emotions I felt and the amount of time I spent as a Care Partner, learning as I went, it’s worth looking at a chart of our Journey showing the phases Sumi went through over time.

The first phase was pre-diagnosis. Looking at Figure 1, there is a green vertical line at April 2013. This line indicates when Sumi was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. But before diagnosis, there are usually one to three years, or more, where symptoms are present. This time, the Pre-Diagnosis Phase, I have marked on the left of the vertical green line.

Then, usually, there is a Trigger Point at which point a formal diagnosis of the disease is sought. In Sumi’s case, she got lost going to a friend’s house. Fortunately, she came home on her own after five hours.

Post diagnosis includes phases 2, 3, and 4. The life expectancy after diagnosis is eight to ten years. However, in some cases, it can range from three to twenty. This depends on various factors, such as age at the time of diagnosis, gender—since women tend to live longer than men, other health problems, the severity of symptoms, and brain abnormalities.

For illustrative purposes, I chose a 10-year life expectancy to chart our Journey. But each person with the disease and their Care Partners have unique circumstances. Some Journeys are going to be totally different than Sumi and mine. There are no hard and fast rules. What fits one situation may not fit others. However, there are many general paths that most PWDs and their Care Partners will travel.

Prior to Sumi’s diagnosis, our relationship was binary and reciprocal. We took care of each other’s needs and there was a mutual dependency. Our tasks of running the house were divided to complement each other’s skills and comfort levels. With the onset of the disease, everything turned upside-down. Our relationship, in most situations, became unidirectional and non-reciprocal. My love for Sumi became more intentional. It is not easy to naturally love when under a lot of stress and when pushed into frustrating situations. In some demanding situations, my reflexes would take over.

Phase 1 — Denial & Anger

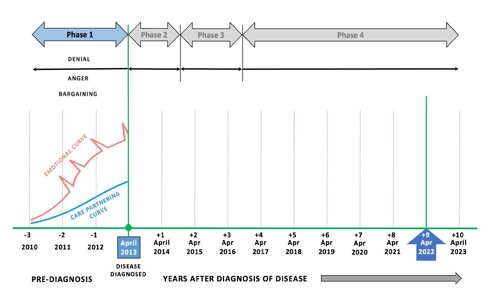

Next, I would like to start charting my emotional and Care Partnering curves. Figure 2 shows my progress in the pre- diagnosis phase.

The Emotional Curve is in red and the Care Partnering curve is in blue. They start at minus three years when Sumi first began to show symptoms but before an official diagnosis.

The vertical, y-axis, has no scale but shows the relative magnitude of emotions experienced by me. This can be used as a reference to Care Partners in general.

|

|

During this time I was mostly in denial. I didn’t want anything to be wrong with Sumi. I was also frustrated and angry as Sumi was not able to perform some simple tasks.

My emotions rapidly increased and were quite intense with many spikes of extreme emotions as time went on. At the same time, the Care Partnering curve began to slowly rise as I had to step in to help Sumi more and more.

Phase 2 — More Denial, Shock & Guilt

In some situations, even when we are well informed and well-read, we still believe what we want to believe. We cling to false hope and are comforted by not having to face reality. This denial, by the caregiver and the person with Alzheimer’s, is very common in the earlier stages of the disease. Many times, I would think: What if the doctor misdiagnosed the disease?

For a couple of years after Sumi’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, I was in denial. Sumi was functioning well and there were no other major issues. Occasionally, when I suddenly discovered evidence of Sumi’s functional decline, the truth of her Alzheimer’s would hit me like a brick, as if I was realizing it for the first time.

Reality Breaks Through

After her diagnosis, her driving was limited to short distances for going to the grocery store or for exercise at the fitness center at Oakland University (OU). One time, a friend told me she saw Sumi looking for her car in the parking lot of a mall near our house. This friend helped Sumi find the car. I wonder how often this must have happened to Sumi and what must have been going through her mind, as she had never told me about such ordeals. I sometimes also noticed minor bumper or fender damage to our car that Sumi was unable to explain.

We used to exercise together at OU. After exercising, if it was cold or a snowy day, I would tell her that I would get the car and she should wait to be picked up by the entrance to the fitness center. When I would pull up near the entrance, she would not recognize the car. I would get out of the car and wave at her and then she would walk toward the car. Sometimes, instead of opening the front passenger door, she would open the rear door to get in.

At home, she had trouble recognizing shapes. When hanging her clothes on the hanger, she hung them sideways. While making the bed, she would use the long side of the fitted sheet on the short side of the bed. When she realized her mistake, she was unable to figure out how to correct it. Luckily, she would remain calm. I was the one who got frustrated noticing her decline.

Sumi used to prepare our dinner ever day.

Her cooking had always been healthy and delicious. As her disease progressed, she started to lose the fine balance of well- proportioned spice levels that Indian cooking requires. Sometimes her meals were too salty or too hot with chili. Eventually she was unable to cook but could help me prep, and I would add the spices.

When a spouse is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, many couples undertake travel right away knowing it might not be possible as the disease progresses. We had been traveling all our lives and continued to do so in the initial years of her disease. But many challenges arose while traveling with Sumi.

In 2015, we had to renew our passports. At the local post office, when we were asked to sign our names on the applications, I signed mine and asked Sumi to sign hers. To which she asked, “How do I sign my name?” I slowly spelled it out loud, but she was not able to follow my instructions to sign her complete name. We had to cancel the visit. At home I signed her name as guardian, and mailed the application. Our passports arrived a few days later.

International travel had its unique challenges. At the security checkpoint, when Sumi was asked to step into the X-ray booth and raise her hands above her head at a certain angle, she could not follow the instructions. Realizing this, I told the attendant about her disease. He called his supervisor and finally a female agent did a manual body frisk and let Sumi proceed.

On flights, I had to accompany Sumi to the restroom. One time she went in the restroom and latched the door and couldn’t figure out how to unlatch it. I had to shout instructions from the outside until, after several attempts, she was able to open it. The next time, when she had to use the restroom in-flight, I wedged my foot between the door and the frame to keep the door slightly ajar. She could still use the restroom by herself. A few months later, on a different flight, I realized that she was unable to use the restroom by herself. I had to go inside with her to help remove her pants. I have no idea what other passengers must have thought. I wanted to wear a T-shirt saying, “My Partner Has Memory Loss.”

Some airports, such as the one in Paris, have family restrooms in the terminal. I would take her in one of those before boarding hoping she would not have to go to the bathroom during the nine-hour flight. I would also limit her liquid intake before boarding. Upon landing, when it came time to fill- in the immigration and customs forms, I realized she could no longer complete them on her own.

Upon landing, when it came time to fill- in the immigration and customs forms, I realized she could no longer complete them on her own.

Our last big trip together was in December 2015 when we went to Los Angeles to visit our children. We stayed with our son in his apartment, and Sumi was unable to adjust to the new, confined place. After a couple of days, she got very agitated and angry repeating in English, “I want to go home! I want to go home!” I had to cut short the visit and return home. As soon as we went to the airport and sat down in the lounge waiting to board the flight home, she said in Gujarati, “Haash” meaning, “What a relief!”

In phase two, I was still in continuous denial. I hoped the neurologist had misdiagnosed Alzheimer’s and Sumi really had mild cognitive impairment.

I began grieving for my old Sumi and felt a great deal of guilt. Through all our lives, Sumi was such a good wife to me. I felt guilty that I hadn’t been a better husband to her.

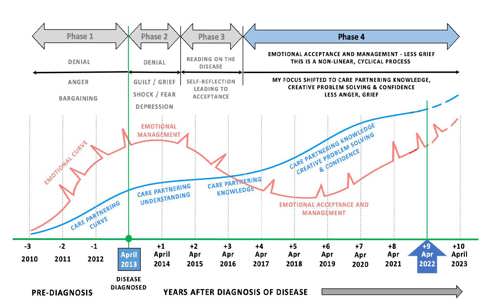

My Emotional Curve during phase two, shown in Figure 3 in red, rose less dramatically but remained high. I was still very emotional but with fewer spikes of extreme emotion.

The blue Care Partnering curve continued to rise steadily. This is because of the strategies and tactics I employed as a Care Partner to take care of Sumi’s future needs. I gained experience and knowledge.

Phase 3 — Research & Reflection

As phase three began, I started reading books about Alzheimer’s. This led me to other types of dementia, such as Vascular, Lewy Body, and Frontotemporal. Sumi’s neurologist had diagnosed Sumi with Alzheimer’s but the brain is a complex organ. I wondered if Sumi might, instead, have another type of dementia. I wanted to dive into research to know for sure, but soon realized that accurate diagnosis is difficult. This is because symptoms are similar among those different types of dementia. Symptoms can also vary from person to person.

Therefore, it did not matter what type of dementia Sumi had. What mattered most was how I could become a better Care Partner. How I could use love, mercy, compassion, and patience to take care of Sumi and what strategies I needed to learn and employ to keep her safe. To me, emotional acceptance and management meant recognizing that Sumi is slowly changing in front of me and sooner or later it will become incumbent upon me to change as well. I learned to differentiate between real and anticipatory grief.

Figure 4 shows my Emotional Curve, in red, is not smooth. There are still sudden emotional spikes but the curve starts to decrease as I gain more knowledge and confidence. I was able to gain some control over my grief. This helped lower my emotional intensity.

The blue Care Partnering curve continues its smooth curve upward as I gain more experience as time goes on. Over time I learned that effective caregiving comes from love, mercy, compassion, and patience.

Phase 4 — Emotional Acceptance & Management

Entering the fourth year and the fourth phase, my Emotional Curve started to flatten out. This is due to me gaining knowledge about the disease (Figure 5).

Now, as Sumi’s 10th year with the disease starts, I can look back and reflect. There were turbulent times over the years when my Emotional Curve would spike up.

For example, on a warm day in October of 2018, Sumi was walking with us at our local park. She side-stepped on the edge of a concrete walkway and twisted her right foot. This caused a hairline fracture in her ankle. Sumi had to wear a removable boot and had to be moved around in a wheelchair.

After six weeks she was on her feet and walking again. The only problem was during recovery she had slowly reduced her eating intake to only a small quantity of food. With no intake, there was no output. On two occasions I had to take her to the Emergency Room to receive an enema to extract the hardened stool.

After six more weeks, Sumi had lost about 25 lbs. I feared her decline would be irreversible. But then, she began to eat more food. It took another week for her BM to come back to pre-fracture status.

These types of ordeals showed me that my emotions are non-linear and cyclical. I had been at a level of acceptance but when Sumi fractured her ankle it triggered anxiety, fear, and frustration. It took a few days, but with the support of Sumi’s caregivers and my own reflections, I was able to reestablish my acceptance of the situation.

Care Strategies & Creative Problem Solving

Throughout our Journey, I’ve been a bundle of mixed emotions. Next, I will unbundle them to show how I have been riding this emotional rollercoaster. I will explain what I have done to mitigate or take control of my emotions. These techniques have helped my Care Partnering curve increase steadily.

The first thing I did was educate myself about Alzheimer’s disease. I read many books and attended classes and seminars on caregiving. This helped me reach a level of emotional acceptance.

I recognized Sumi is not a problem to be solved but a person to be loved and cared for deeply with compassion, patience, and mindfulness. As Sumi changed, it became incumbent upon me to also change. I needed to change my perspective. I began to differentiate that when Sumi is extremely difficult it is not her, but the disease. When she is smiling it is her true self and not the disease.

Part of reaching out for help is receiving and giving support. I attend two support groups which provide an outlet to openly share my feelings. I also get to learn from others and share my own experiences. Fellow caregivers tell me they find comfort and inspiration from my experiences and writings.

To help educate myself, I took a class called “Powerful Tools for Caregivers.” It was offered by the Area Agency on Aging 1-B. I learned many strategies and tactics to become an effective caregiver.

I also attended a seminar by Teepa Snow, one of the world’s leading educators on dementia. This provided me with a deeper understanding of Alzheimer’s.

I gained wisdom through contemplation, understanding the impermanence in nature, mindfulness—learning to live in the present, finding a sense of equanimity and proportion, writing about my experience, and sharing our Journey with others.

For self-care, I attend “Art of Caregiving®” classes offered by the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center (BBAC) of Michigan. We learn different forms of art as an outlet for expressing ourselves. During class, I get so engrossed in the projects, I momentarily forget about caregiving. (I have included some of my artwork from the BBAC throughout this book.)

When it comes to Sumi’s care, I have built a team of professionals to provide one- on-one, person-centered care for Sumi’s well-being and safety. This includes Sumi’s doctors, caregivers, and a few friends. I arrange with Sumi’s caregivers to help with her daily chores, like toileting, bathing, dressing, feeding, etc. I take care of legal, financial, and medical matters.

Another important thing I have done to help Sumi’s care is practice Kaizen. In the Japanese language, Kaizen (改善) refers to the continuous improvement of all functions and processes. I have been looking for ways to improve daily tasks to help Sumi’s safety and well-being. I provide creative solutions to problems that arise.

For example, I installed cameras in the house to monitor Sumi’s movements. I also installed a motion sensor alarm in the bedroom so when Sumi tries to get out of bed I am alerted or awakened to help with her needs. This allows me to sleep calmly and not subconsciously monitor her in my sleep.

I also covered all the mirrors and reflective surfaces in our home to avoid Sumi’s confusion when she looks into them.

I noticed while eating at night that the interior of the kitchen is reflected on our sliding glass doors. Seeing her own image, my image, and other reflections in this “mirror” Sumi would get distracted. So, I installed a pull-down blind and the problem was solved.

TV images and voices bother Sumi so I stopped watching TV in her presence and cover the TV screen with a cloth.

Other solutions I have implemented are things like changing the carpet in the bedroom to a hardwood floor so toilet accidents are easier to clean. This reduced my anger and frustrations.

I put soft foam pads on any surfaces Sumi could bump into. When Sumi was able to walk in the basement, I covered all the structural columns with soft pads in case she ran into one of them.

Kevin Conway, my daughter Parini’s husband, designed and built a ramp in the garage to help Sumi get in and out of the house. Years back, Sumi enjoyed walking in our local park. As her disease progressed that became too difficult. So now, on nice days, I take her outside in her wheelchair. Having a ramp that goes from the house to the garage makes it much easier to navigate her wheelchair in and out of the house. And when I take Sumi out, the ramp provides an easy way to lead Sumi out of the house and straight into the passenger front seat as the open car door is lined up with the end of the ramp. When we get home, she can get out of the car and walk straight up the ramp to get inside.

I installed another ramp with the aide of a handyman to help Sumi navigate from the foyer to our sunken family room. As Sumi walked inside the house, the 6” drop posed a potential tripping hazard. When I built the ramp, Sumi was very comfortable navigating from foyer to living room and the other way around. As her disease progressed, though, it became too difficult for her to use the ramp and I dismantled it. One thing we Care Partners learn is what works at one time may not work later on.

During meals Sumi would fidget and move her plate, making it hard for her to eat.

|

Garage Ramp |

|

Sometimes, frustrated, she would even throw her plate from the table onto the floor, food and all. While searching for a solution I found a place mat made by a British company called Dycem. The place mat not only sticks to the table but sticks to whatever you put on it, keeping it still. Now, Sumi’s plate doesn’t move. She is less frustrated and can eat from her plate. I highly recommend this place mat for anyone with small children or people with special needs.

A problem I’d been facing in the shower was when Sumi would accidentally reach out and turn the knob that controlled the water temperature—or sometimes she would wiggle the water hose which would then move the knob. This splashed her with cold or scalding hot water. I looked into buying a temperature control knob, which is often seen in European homes and hotels. Those types of controls are expensive, require a plumber to install, and could easily cost $1,000 in parts and labor. After brainstorming with a friend, I came up with a simple solution that would only cost $1.48. I bought a 4” PVC plumbing coupling, cut it to the right length, and glued it to the backplate of the shower knob to protect the knob from being accidentally turned. Now that problem is solved.

For a long time, I and then Sumi’s caregivers showered Sumi while she stood in the shower stall. Gradually, she had difficulties standing and wanted to sit. After some research, I bought a shower chair, which has been a blessing.

As shown below in photo A, we make Sumi sit in the chair outside of the shower stall and fasten a lap belt. Then, shown in photo B, we use the swivel mechanism to rotate the seat 90˚ anti-clockwise. After that, we slide the seat with Sumi on it into the shower stall, photo C. The seat can slide up to 20 inches. After showering, the process is reversed and Sumi gets up from the chair outside the shower stall.

As Sumi’s disease progresses, falls resulting in serious injuries are inevitable. As a safeguard, Sumi’s caregivers and I put wearable safety pads on her. These include a foam padded cap worn by lacrosse goalies, a hip protector, and a foam padded wrap- around worn by motorcyclists.

I am never at a loss for problems to solve.

And this problem-solving aspect of being a Care Partner gives me small victories. As I test my solutions, it creates a safer and more comfortable environment for Sumi. I consider my efforts a form of self-care, as it temporarily takes my mind away from the caregiving chores.

Kaizen (改善) has become a watchword for me. As Sumi changes, every challenging situation provides a new opportunity to become a more effective Care Partner by drawing from my career as a problem- solving engineer.

Looking back at my Emotional Curve (Figure 5), something to note is that for the more emotionally inclined Care Partner, the area under the emotional curve will be larger. The opposite also holds true—a Care Partner who is less emotionally inclined will have a smaller area under the curve.

For the care partnering strategies curve, a Care Partner with more knowledge and understanding of the disease will show a larger area under the curve. And a Care Partner with less knowledge will have a smaller area under the curve.

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease. It gets worse as time goes on. In the final stage, the brain’s functions could deteriorate so much that it fails to instruct the mouth to chew and swallow. This results in more complications and a deterioration in health. When this occurs, it will heighten a

Care Partner’s distress as they will see the ultimate demise of their loved one.

Knowing this, I try to prepare myself for the eventuality. But I also know that “one is never prepared for this tragic moment.” The sad reality is Alzheimer’s always wins.

Assuming I survive Sumi, I will enter another unknown phase of my life. I did not volunteer to play the role of Sumi’s Care Partner; it was thrust onto me. And once she is gone I wonder what my life will look like. I’ve heard from other caregivers whose loved ones passed away that they are scared to form new relationships. The fear being, what would happen if the new partner develops some form of dementia? Would there be enough physical, mental, emotional, and financial capacity to take care of this new loved one?

|

|

These thoughts have not escaped me. Considering life’s twists and turns and its ambiguity, the only thought that comes to mind at this moment is how I would like to utilize all the knowledge and skills I’ve developed by devoting myself to helping others navigate their own caregiving Journeys with less pain.

I consider myself fortunate. I am in a good physical, mental, emotional, and financial state. This allows me and Sumi’s caregivers to provide one-on-one, person-centered care in our home.

The hardest part of caregiving is that it is a lonely journey. Even with tremendous support from family and friends, it is easy to still feel alone. I feel as though all my dreams and hopes are on pause.

Sometimes I feel like I’m at a cliff’s edge. But with steadfastness, I amaze myself and continue to climb to new heights with respect to my caregiving. What I thought was a cliff was really just another plateau—a new normal.

Changes in Sumi have precipitated changes in me and opened up new internal vistas. Sumi gives my life purpose, clarity, and focus. I strive to become a better person and husband by being more loving, caring, compassionate, and patient. This allows me to maintain my emotional equanimity and mindfulness. I am able to recognize the important things and let go of the trivial. I try to control the controllable and manage the uncontrollable.

My anxiety, stress, and blood pressure have been reduced, improving my well-being. I find that I am compassionate, self-healing, a little wiser, and at peace with myself.

The final thought I would like to leave you with is that loving someone with Alzheimer’s is like living in two worlds. The first is who the person is before the disease, my first Sumi or Sumi1.0. But as the disease progresses it’s almost as if you have to get to know an entirely different person. This is my second Sumi or Sumi 2.0.

Both of these worlds co-exist simultaneously, like two banks of the same river. Sumi 1.0 and Sumi 2.0 are each a bank. It is extremely painful to live in both worlds. I can’t just lock up the former world— with my first Sumi—in the deep recesses of my mind and forget about it. And at the same time, I can’t ignore the real world with my second Sumi.

After a long struggle, I have figured out my well-being depends on smoothly navigating between these two worlds with a balanced mind. I try not to get overwhelmed by either of them. It is like crossing a rickety suspension bridge over a turbulent river when I’m not even sure I want to get to the other side to visit Sumi 1.0. But with determined resolve, I do cross it and navigate between the two banks of the river all while maintaining my equanimity.

In our Journey, I have come to realize that grief is not the process of forgetting or suppressing memories of Sumi. Instead, I remember those memories at will or on special occasions, with less pain.

The common thread in my two worlds is Sumi’s smile. Every day I try hard not to let that go.

I must acknowledge and introduce Peggy and Selina (lower left and right, respectively) who care deeply for Sumi and me. Without their professional care and love, Sumi’s Journey would be very different. Also my sister, Kailash (upper photos), who three years ago stayed with us for about six months and provided so much cheer to Sumi and I.

|

|

|

|