Monday, March 23, 2020—9:30 am 32˚F (0˚C)—Snow f lurries

On March 20, a freelance writer for The New York Times contacted me. She was interested in doing a story on my wife, Sumi, and me. Sumi was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at 59. She will be 66 in May. The reporter’s main focus was what is our current routine and how has it changed due to the coronavirus pandemic?

To prepare for my interview, I wrote the following:

With Covid-19, we live in uncharted and trying times and are all hunkered down in our houses. No matter what part of the world you live in, the story of Covid-19 is the same . . . social isolation, social distancing or societal lockdown.

It occurred to me that by circumstances, Sumi and I (and millions of other persons with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers), have been practicing social isolation and to some extent social distancing on an ongoing basis. Sumi and I have for the last three years. Ours is a lonely journey, in spite of getting tremendous support from family and friends. I have limited social interaction compared to what we used to have, and Sumi is in daily contact with only three people.... me, and her two part-time caregivers.

Our limited social interaction is good news with regard to the risk of getting coronavirus. However, the fickle mind conjures up various scenarios in which either Sumi, or me, or we both get this virus. In one scenario, I could get it when I go out to buy the essential food items and then pass it on to Sumi. In the other scenario, one of Sumi’s two caregivers gets it and they pass it on to Sumi and then we all get it. In any scenario, it is verylikely that we all are at very high risk if

any one of us gets it. Another scary part is coronavirus can be asymptomatic.

Sumi’s evening caregiver has another job in a nursing home, and I consider that she is at very high risk. (About five days ago, someone in another nursing home in Rochester Hills, Michigan, where we live, tested positive). On Friday, (Mar 20), Sumi’s evening care giver and I had a very open and candid discussion about my concern of her being at high risk. We both agreed that she would take a week off until March 29 and we will re-assess the situation then. She is financially okay as her work is very much in demand and she can easily make up the lost hours by working extra hours at the nursing home. I paid her a percentage of what she was making even though she will not be coming to take care of Sumi.

Over the years, Sumi has migrated to the third and final stage of her disease, as defined by the Alzheimer’s Association. She cannot control her bladder and bowels (she is incontinent), she needs round-the-clock assistance with daily activities (such as toileting, daily bathing, dressing, grooming, feeding, cleaning, and so on). She has lost awareness of recent experiences as well as her surroundings and she is not able to communicate her needs, discomfort and pain. However, Sumi is physically fit without any other ailments or needing any medications. She eats well and walks about three to four hours in our basement every day.

While taking care of Sumi, I cannot keep a safe distance from her. When she gets agitated, I hold her one hand, put my other hand behind her neck and caress it and pull her head upward to give her a kiss on the forehead or cheeks. This calms her down. For her it is a Kiss of Love. For me it could be the Kiss of Coronavirus (from me)!

LIKE AN ORCHID

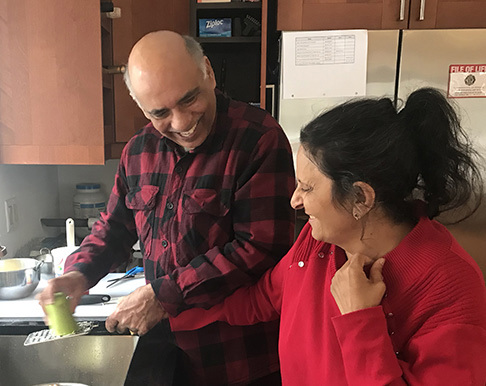

If Sumi and I are infected simultaneously, what would happen if we got quarantined separately? Would we be quarantined at home or taken to the hospital? If at home, I may not be in a position to take care of her. Who would, then, take care of Sumi? As is the case with many persons with Alzheimer’s disease, Sumi has forgotten her learned language (English). Hence,she needs to be communicated in her first language, Gujarati (one of India’s languages). She gets a special diet that is high in fruits and vegetables and has no meat. She gets a three-berries fruit smoothie every day. We shampoo and wash her hair every day, apply hair oil, and either braid her hair, do a ponytail, or a bun. She finds it reassuring and thoroughly enjoys it. How will she get all that?

Sumi gets one-on-one, person-centered care at home. Sumi is like an orchid plant. Orchids need to be watered very carefully with one ice cube a week. The ice cube melts slowly and gives the orchid a slow drip of hydration, so that it doesn’t drown in it. This finely calibrated and cultivated daily routine of Sumi’s engagement and enjoyment would be totally disrupted. I am fortunate that I have Power of Attorney and Guardianship for Sumi. But if we are quarantined separately, how would these legal documents be verified as Sumi cannot give her consent for a medical procedure.

At home we observe her every moment. We have become super detectives in deciphering her body language, her needs and her requirements before they arise. She is calm and congenial most of the time. But in the new surroundings in the hospital she may get agitated, non-cooperative and combative. In that case, would they sedate her, give her anti-psychotic drugs? In the past, I have heard stories from other caregivers that when their loved ones with the disease were taken to the hospital for an extended period, they got totally messed up when they returned home. Some even declined faster and could not survive the trauma of such an experience. With all this weighing on my mind, I wonder if our medical system is equipped to take care of a person with Alzheimer’s like Sumi. Who would give “one ice cube” to my Sumi and not drown her in medications? Who would play the role of super detective in Sumi’s life at the hospital?

Over the last seven years as a care partner, many times I felt as though I was on a cliff’s edge. But with steadfastness, every time, I amazed myself that I managed and scaled a new height in caregiving. What I thought was a cliff was just another plateau - a new normal. But now I am uncertain of what this new normal will turn out to be.The care I have for my wife, along with other caregivers, is like a single-pole tent. It is scary to think what would happen if this pole crumbles.

After the interview, the reporter asked me what happens if this virus goes on for a long time and both Sumi and I are seriously ill.

I told her I believe in the impermanence in nature of everything that is born and living. If we ever come to that stage of illness due to coronavirus, I am not overly worried and consumed by it. As a care partner of Sumi for the last few years, mindfully, I am taking one day at a time and I will continue to do that as long as I am able to do it. Writing down my concerns, worries and fears, helped me channel and process my feelings, document the threats and share these with The New York Times reporter.