Wednesday, November 13, 2019, 21°F (-6°C), Cloudy and cold.

Lipsa Sheth, Founder and Publisher and Maitreyi Anantharaman, Managing Editor of the Indian Scene will be publishing a two part article on Sumi and me and Alzheimer's. The part one appeared today in the Indian Scene.

The Indian SCENE tells the stories of Indian-American life in and around the Detroit area. The monthly online culture and lifestyle magazine features profiles of most accomplished and interesting community members, deep dives into the health issues facing Indian-Americans, the wisdom of our eldest pioneers, the voices of our next generation and more.

Love, Care and a Life-Changing Diagnosis: A Story of Alzheimer’s Disease

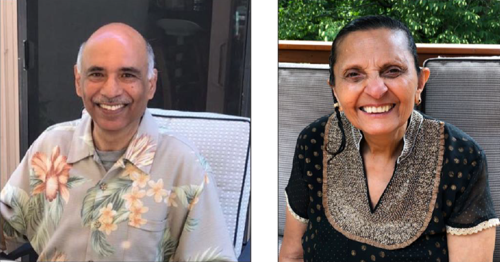

In this two-part series, we follow K.C. and Sumi Mehta as they navigate the new emotional and logistical realities of Alzheimer's disease.

Maitreyi Anantharaman

November 2019

Alzheimer's, Alzheimer's awareness, Alzheimer's disease, Alzheimer's support, Featured, K.C. and Sumi Mehta

Sumi Mehta’s husband was worrying about her. It was 2013, and he had begun to notice small, suspicious lapses—a missed exit here and there, taking a few moments longer than usual to change lanes or make turns. Sumi drove to the party anyway, or at least, she tried. Forty-five minutes after she left to attend a family friend’s birthday celebration, K.C. answered a call from his wife, who had gotten lost about a mile away from her destination. He tried explaining the route, and then didn’t hear from Sumi for hours. Friends went looking for her; K.C. called the police, too. When a distraught Sumi found her way back to the couple’s Rochester Hills home, hours later, K.C. could not bring himself to ask where she’d been.

Shortly after the driving incident, K.C. and Sumi went to see a neurologist. Sumi, then 59, told the doctor she had been forgetting names and details. Months before, she had left the stove on. Simple arithmetic had become difficult, too. To measure memory function, their doctor administered a series of standard tests. Could she remember three words and recall them a few minutes later? Could she answer basic addition and subtraction problems? Did she know the names of past presidents or the prime minister of India? What was a television show she watched, and could she explain what it was about? She had difficulty with all of those.

An Alzheimer’s diagnosis, K.C. says on one October morning, provides practically no room for hope. A cancer patient’s hair may fall out, they may grow frail, but some comfort can be taken in the fact that they remain the same person, just a balder, frailer version. Even at their lowest, most difficult moments, their traits and curiosities and inner lives will not wither away; there is even the chance they recover completely. But what can you tell a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, a form of dementia estimated to affect 5 million people in the U.S.? It is marked by irreversible cognitive decline, with symptoms that worsen over time. There is no cure, no way to stop or slow its progression. Why her? K.C. wondered when he learned the news.

At this point, K.C. says, over six years since Sumi’s diagnosis, he feels like something of a veteran caregiver. In support group meetings he attends, he finds himself lately being a source of advice to others, rather than needing it himself. Had he always been so calm, I ask him, perplexed by his composure in the face of a difficult situation. No, K.C. says. It was a “long struggle” to achieve the sense of peace he feels now. There was anger at first; it can be frustrating to take care of Sumi sometimes. But he has resolved to live in the present, knowing that the pain and grief dredged up by memories of the past can be channeled into some kind of motivating force. He is intensely contemplative these days, and shares his reflections in an ongoing series of messages to friends and family members he calls “My Journey with Sumi.” Through the writing, he hopes not only to chronicle his own growth, but also to inspire self-reflection and change in others.

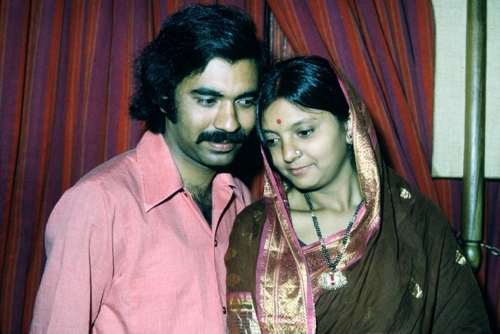

In one installment at the end of 2017, he describes his upbringing in a competitive Indian society, one that tends to foster “alpha male” attitudes. After Sumi was first diagnosed, K.C. wondered, with some guilt, whether he could have been a better husband to Sumi, a devoted and compassionate wife whose primary concern after being diagnosed was for K.C. He has decided that the only thing he can do now is to act in his wife’s service. A book he read posited that when a person has Alzheimer’s disease, they do not lose their capacity to give and receive love. He suspects this is true of his wife. When Sumi kissed K.C. on the lips but knew to kiss a family friend on the cheek recently, K.C. took that as a special sign.

Describing K.C. as “left-brained” might be something of an understatement. He is an engineer by training and a former corporate consultant; when he writes and speaks, it’s as if he’s delivering a tidy, methodical lecture. His chronicles of life as a caregiver to Sumi sometimes read as a student’s notebook — he reflects on books he’s read and summarizes them in detailed bullet points. He likes to illustrate concepts and processes through lists and flowcharts, describing anything from the stages of Alzheimer’s disease to the five “love languages.” He calls himself a career problem-solver; even in retirement, that hasn’t changed. What has changed, though, is that he’s found himself drawn to his creative side. With other caregivers he talks to regularly in support groups, that shift is not uncommon.

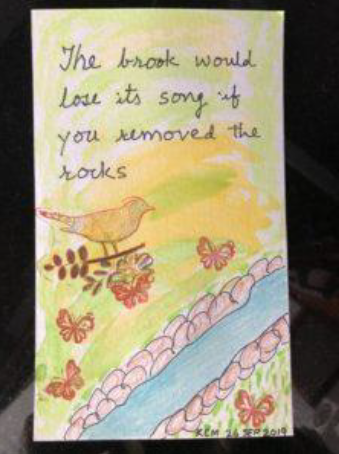

The arts, researchers say, can provide caregivers with a temporary respite or means of stress relief. K.C. started with short poems, which have graduated into the long, meditative essays he pens for “My Journey with Sumi.” Last March, he began taking art classes for caregivers at the Birmingham-Bloomfield Art Center. “I get so engrossed [in] the art class doing the art projects that momentarily, I forget the trials and tribulations of care giving,” he wrote recently in a message to friends and family members. Among other projects, K.C. has drawn an adorable ostrich in oil pastels and bound a painted book using the Japanese stab-stitch. Sumi has put the pen in his hand and given him an unlimited supply of ink, he wrote in an installment of “My Journey with Sumi” last year. “I am just the instrument.”

At times, existing in a state of composure and acceptance can feel astoundingly lonely. Loneliness is an increasingly common feeling among adults, but it is magnified for family caregivers, who have devoted their lives to one person. Sumi does not recognize the couple’s adult children or other family friends. She has provided her husband with purpose and focus, he says, but it is sometimes difficult for him to have so few people to talk with. K.C. says he might be the only one so far who has been able to make peace with the existence of two Sumis, and likens that process to crossing a rickety suspension bridge between the banks of a river. “The common thread in my two worlds is Sumi’s smile,” he writes. “Every day, I try very hard not to let that go.”

Next week, we’ll follow K.C. and Sumi as they live in their new normal.

Alzheimer's, Alzheimer's awareness, Alzheimer's disease, Alzheimer's support, Featured, K.C. and Sumi Mehta

Magazine's Editor

Adjusting to a new normal: a story of Alzheimer’s disease

In this two-part series, we follow K.C. and Sumi Mehta as they navigate the new emotional and logistical realities of Alzheimer's disease.

Maitreyi Anantharaman

November 2019

This is the second of a two-part series from The Indian Scene. Last week, we told the story of one family and a life-changing diagnosis. This week, we’ll follow them as they navigate their new normal, and explore the financial and logistical realities of Alzheimer’s and caregiving.

A difficult thing about Alzheimer’s disease is that it follows no particular template. Symptoms and their timing and severity will vary across patients; how and when certain motor and language problems start to appear, for example, are specific to the individual. For that reason, K.C.’s caring for Sumi requires a Japanese management strategy he cites called kaizen, the “continuous improvement” of processes and functions, every routine tweaked and modified to best serve Sumi’s needs. At the Mehta house in Rochester Hills, where K.C. and Sumi are hosting The Indian Scene on an October weekday morning, that’s on full display.

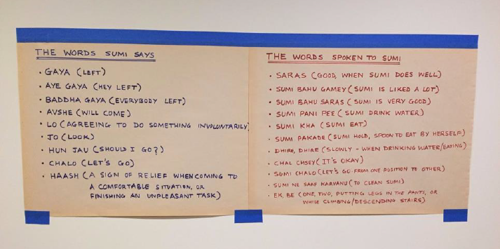

The language of Alzheimer’s disease, K.C. says, is “said but unsaid.” After decades of marriage to Sumi, he can pick up on body language and subtle facial expressions; sometimes, that’s all he has to work with. As is the case with many Alzheimer’s patients, Sumi’s ability to remember her second language — English — has been mostly lost. Instead, she communicates in fragments of Gujarati, her native language — not quite enough to construct a full sentence, but enough to communicate basic needs. On a poster in the Mehtas’ kitchen, K.C. has neatly written handy phrases and key words she often says or is receptive to. “Sumi, chalo” (Sumi, let’s go) one might say to her. “Lo,” (OK) she might reply, resigned. Sumi’s caregiver Peggy, a quick learner, has learned an impressive amount of Gujarati in her time with the Mehtas. That morning, after bathing Sumi and dressing her in a simple red sweater with brass buttons, Peggy tells Sumi in Gujarati that she looks beautiful. In a large walk-in closet, K.C. helps to brush Sumi’s hair, soothing and reassuring her when she winces in pain or attempts to get up from her chair.

Sumi took some time to warm up to Peggy, initially distrusting her, but now Sumi greets her with big smiles. It is tremendously helpful to have a professional caregiver around the home, K.C. says. Some families consider placing family members with Alzheimer’s in outside care facilities, but at such a facility, there can be less willingness to adapt to a patient’s needs. Comforts like flexible routines or caregivers willing to speak in a patient’s native language are more difficult to come by, which is why K.C. preferred that Sumi be cared for at home. Admittedly, that isn’t always a choice families can make.

In-home caregiving can be expensive (as a caregiver K.C. knows put it, How can I pay a caregiver $20 an hour when I make $12 an hour?). K.C. is fully retired and is able to spend his days at home, too. For partners who are still working or cannot afford to take time off, there may be other considerations at play. Still, in America, as the population ages, home health care is the fastest growing job category. It is also one of the most demanding, especially relative to what it pays. Around the household, Peggy does a little bit of everything, preparing Sumi’s breakfasts and meals, cleaning her and making sure she’s accounted for at all times. K.C. remembers when Peggy first came to their home and immediately pointed out some safety risks around the house. A set of knives shouldn’t be kept at an accessible location in the kitchen, Peggy said, because Sumi could hurt herself.

Creating a safe home — adult-proofing, one might call it — is a crucial step for caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. As K.C. details in “My Journey with Sumi,” the caregiving diary he shares with friends and family members, the experience has a strange way of pointing out just how many parts and pieces are in a home, waiting to make trouble. When Sumi was given showers, she would often try toggling the knob that controlled water temperature. K.C., ever the problem-solver, experimented with PVC coupling, and glued it on the knob’s back plate. When Sumi struggled to keep her bowls and plates on the table during meals, K.C. found a brand of sticky placemats. And when Sumi saw her reflection in a glass sliding door (mirrors can cause anxiety for dementia patients who may not recognize their current selves), retractable blinds solved the problem. At the Mehta home, K.C. demonstrates a motion sensor alarm that sounds when Sumi tries to leave the bedroom at night.

As late as 2017, Sumi and K.C. could go out to eat at restaurants. Now, though, Sumi is fed at home by Peggy or K.C. Nutritious meals can be a challenge, and most experts recommend preparing food in bite-size pieces and presenting it so that it contrasts from the plate, as spatial abilities and depth perception are diminished for dementia patients. For breakfast and dinner, Sumi eats plates of chopped vegetables, cucumbers, carrots and bell peppers, served with chestnuts and Babybel cheese. Every day, Sumi drinks a smoothie of spinach and methi leaves, carrots, cucumbers, celery, ginger, bananas, raspberries, blueberries, blackberries, orange juice, dates and honey. K.C. makes it in large batches, and keeps them in frozen tumblers.

In a March installment of “My Journey with Sumi,” K.C. reflects on the Buddhist ideal of “equanimity,” perfectly calibrated, unshakeable composure in the face of life’s difficulties. One can voluntarily achieve that state, he writes. Or, like he was, one can be thrust into it. K.C. has come to understand that caregiving is all about that balance, between the practical and the emotional, between longing for the past and living in today’s reality. In typically fastidious fashion, he developed an “emotional curve,” describing his journey in phases. It begins before the diagnosis, when symptoms begin to show, with denial and anger; crescendoes into shock, guilt and grief, before tempering into moral acceptance, a shift toward accepting one’s responsibilities as a caregiver and devoting oneself wholly to their partner. Still, that takes several years.

The best analogy for his caregiving now, K.C. says, is helping someone to scale a mountain. As a person climbs, their survival is in the hands of sherpas, who briefly become the most significant people in their lives, maybe more important than their loved ones. A sherpas prepares the route to follow, fixes ropes in place, carries the necessary tools and supplies up the mountain. On average, they carry loads equal to 90 percent of their own weight. The sherpas do the path clearing and heavy lifting, safeguarding another life along the way.

In K.C.’s journey with Sumi, there is never a dull moment. It is a fascinating, difficult mixture of creative problem-solving, emotional management and continuous improvement. In his seventh year of caregiving, K.C. seems to take the challenges in stride. As he wrote on a drawing he made in an art class for caregivers, “the brook would lose its song if you removed the rocks.”